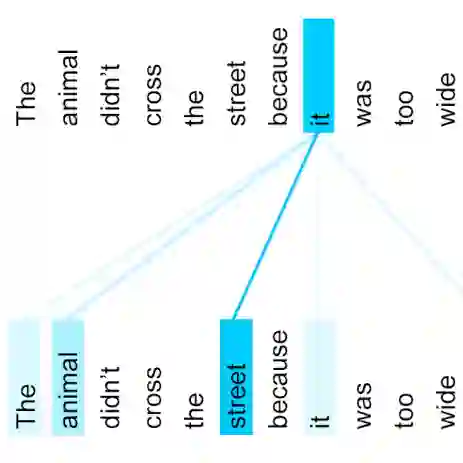

Why do models often attend to salient words, and how does this evolve throughout training? We approximate model training as a two stage process: early on in training when the attention weights are uniform, the model learns to translate individual input word `i` to `o` if they co-occur frequently. Later, the model learns to attend to `i` while the correct output is $o$ because it knows `i` translates to `o`. To formalize, we define a model property, Knowledge to Translate Individual Words (KTIW) (e.g. knowing that `i` translates to `o`), and claim that it drives the learning of the attention. This claim is supported by the fact that before the attention mechanism is learned, KTIW can be learned from word co-occurrence statistics, but not the other way around. Particularly, we can construct a training distribution that makes KTIW hard to learn, the learning of the attention fails, and the model cannot even learn the simple task of copying the input words to the output. Our approximation explains why models sometimes attend to salient words, and inspires a toy example where a multi-head attention model can overcome the above hard training distribution by improving learning dynamics rather than expressiveness.

翻译:为什么模型往往会使用突出的字眼,而在整个培训过程中这种变化如何?我们把示范培训作为一个两个阶段加以比较:在培训初期,当注意的份量一致时,模型学会将单个输入的单词`i'翻译成`o ',如果它们经常同时发生,后来,模型学会了关注`i ',而正确的产出是美元,因为它知道`i'将`o'翻译为`o'。要正式化,我们定义了一个模型属性,“翻译单词的知识”(KTIW) (例如知道`i'翻译为`o'),并声称它推动人们了解注意力的学习。这个说法得到以下事实的支持:在了解注意机制之前,KTIW可以从共同发生统计学到`i ',而正确的产出是美元,因为它知道`i'翻译为`o ',而正确的产出是`o'。我们可以构建一个培训分布,使KTIW难以学习,注意力的学习失败,而模型甚至无法学习将输入输入产出输入词的简单的任务。我们的近似模型解释了为什么模型有时会用突出的词语来学习,而不是学习多动的动态。